I started swimming lessons with a private instructor a week ago. I know how to swim—I love it, actually—and for the last eight months, I’ve been swimming at a local pool here in Lisbon about two to three times per week. Ever since I learned how to swim at the age of 4, I have spent about 10 days every summer in the Adriatic Sea. While in Bali this past September, I joined a swimmers' group called the Amed Stingers and loved our 7 a.m. swims with the majestic Agung volcano looming over us as we did our 45-minute swim along the coast.

I enjoyed ocean swimming so much that I thought I’d look for a swimmers' group here in Portugal. I found a company organizing swimming holidays that said I might be able to join their weekly group in Cascais (a seaside town about 30 minutes west1 of Lisbon)—but first, I’d need to come for an assessment. They offered a wetsuit rental (for a hefty fee) and charged for the assessment. I decided to give it a try. So, on a Sunday morning a few weeks ago, I joined a group of ocean swimmers and an instructor who would assess my swimming ability.

I told them I was a confident swimmer, though I only knew how to do the breaststroke, and hoped that would be okay. They asked me to swim up and down the coast as the instructor walked along the beach. The sea was somewhat rough, and I had to battle the waves, but I kept up, swimming as fast—if not faster—than the six women in the regular group, all of whom were doing freestyle. After six lengths, I felt great being in the water, despite the waves and some floating plastic debris. But when I got out, the instructor told me I wouldn’t be welcome in the group since I didn’t know how to do the crawl. I felt deflated but also determined not to let that experience discourage me from ocean swimming in Portugal.

I decided to sign up for swimming lessons at my local pool, where I’ve been swimming my 40 lengths in the 25-meter lanes since March. I went for a package of eleven 45-minute private lessons (it included a 10% discount, I do love a good deal). I was excited and proud to be doing this at 50, though I did wonder if I was “too old” to be learning something new.

On my first day, I met my instructor and told her in Portuguese that while I speak the language, I might be too stressed to follow the lessons entirely in Portuguese. She immediately switched to English and said, “No problem; we’ll do it in English.” She asked me to show her my breaststroke and then had me grab a floating device to start practicing freestyle breathing, putting my head in the water. To put it mildly, I did not enjoy it. While I have no problem breathing out underwater with breaststroke, this new technique left my head spinning. I kept opening my mouth at the wrong time, swallowing water, and burping from all the air and water I took in.

At the end of the 45 minutes, I asked the coach if there was hope for me to learn, and she smiled, saying, “Of course.” I decided it that was a good sign and not just a polite response of someone who has been paid to do the job. We set up another lesson a couple of days later. That time, I was even more tense and swallowed even more water. I was out of my depth, frustrated, and mentally exhausted. The coach offered different exercises to help me relax, and I did them diligently, but I was still tense, short of breath, and swallowing a lot of air (and water).

By the third lesson, the instructor tried to make things easier, noticing my discomfort, which only made me feel embarrassed. I don’t like to appear weak—I’ve always prided myself on being strong and capable, perhaps to my own detriment. The water in my ears didn’t help, and I tried to distract myself by thinking of writers I admire who are swimmers—Deborah Levy, Colombe Schneck, and Nina Stibbe—but it was no use; my inner critic was still loud, reminding me they not only write exquisitely, but are also good swimmers. Afterward, I went home exhausted and relieved to see that the pool would be closed for a public holiday that Friday, giving me a break.

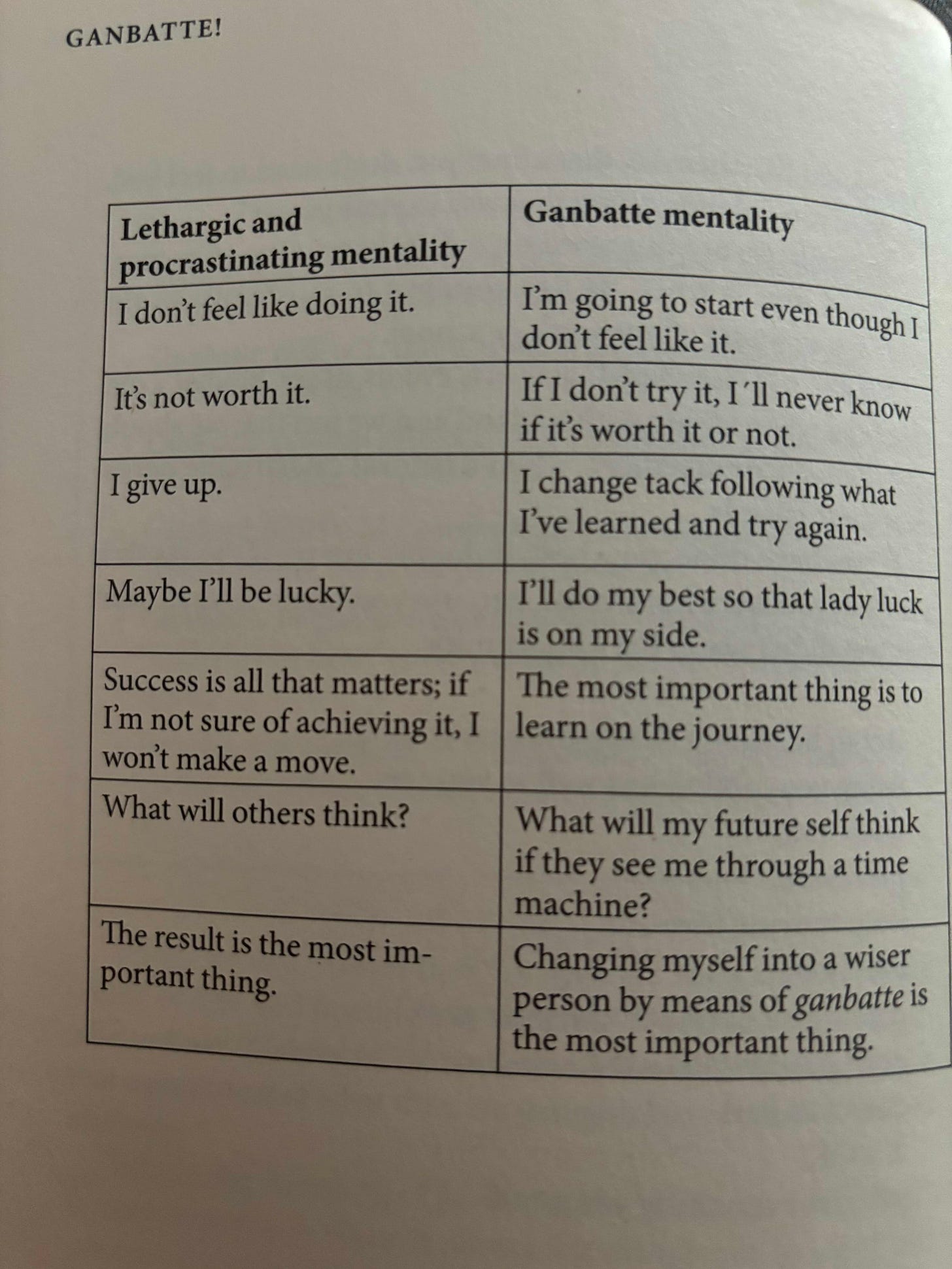

Now, here’s the part I really want to talk about: grit and perseverance, and knowing when to let go of expectations. In Bali, there were days when the current was strong, and I had to dig deep to finish the swim. And on that same trip I came across a little book on the Japanese concept Ganbatte.

Ganbatte (頑張って)2 is a Japanese phrase that roughly translates to "Do your best" or "Hang in there!" It’s used as a way to encourage someone to persevere, work hard, or stay determined in the face of challenges. It’s often said to people who are about to take on a difficult task, face an exam, or participate in a competition.

Ganbatte is more than just a casual wish for good luck—it implies effort, resilience, and persistence. In Japanese culture, ganbatte embodies the spirit of persistence and dedication, which are highly valued qualities. You might also hear variations like ganbatte kudasai (a more polite version) or ganbare (a more informal, direct version). It emphasizes trying your hardest, even if the outcome is uncertain.

I’ve written before on Substack about the importance of knowing when to quit. Today, however, I’m thinking about knowing when to keep going. It would be easy for me to quit learning freestyle now. Sure, I’d lose some money, but I could spare myself more difficult moments in the water, and I’d be giving in to the voice in my head saying, “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.” But another part of me says, “You can do this, and you’ll regret it if you don’t give it a real try.”

In his work on regret, Daniel Pink found that people often regret the things they didn’t try more than the things they pursued, even if they didn’t succeed. I don’t want to look back and think I didn’t give it a go. So, in the spirit of ganbatte, I’ve scheduled my next swimming lesson and bought ear drops to deal with swimmer’s ear. I’ll keep learning to crawl and try not to get attached to the outcome, though it is hard to let go of the wish to learn this technique. And while I do it, I may explore my need to do things well and not come across as weak or incompetent. There is definitely work to be done in that area of my life.

Do you struggle with learning new skills or stepping out of your comfort zone? What’s something you’re determined to keep pursuing, even though it’s challenging? Or maybe there’s a goal you took on later in life that’s tested your perseverance. I’d love to hear about your experiences in the comments. And if you have any swimming tips to help me along, please share! As always, thank you for reading.

Note that I have originally written that Cascais was located east of Lisbon. It is, in fact, west of Lisbon.

I asked Chat GPT to help with the Japanese spelling, so if any of my readers are Japanese speakers, let me know if this is spelled correctly.

Hey, Liza. Thanks for sharing. It is really difficult to try new things. Last year I started horseback riding lessons, which has been a childhood dream. It turned out to be much more difficult than I though. But I'm making progress and taking all the opportunities to improve, despite my constant moving across continents. I think it's important to set small targets to ourselves and to celebrate the small wins. With time, we see that the big goal is not that far anymore. Keep going!!!

This story reminded me of how I improved my swimming while living in Cambodia, Liza. My son, who was then 4 said "Mum, you swim like a granny. You have to put your head under water!" He was right. I could swim, but I'd never learned properly. I went through panic and discomfort. But I finally managed a decent breaststroke with proper underwater glide. But, I still didn't crack the crawl. This has just reminded me I should have another go!